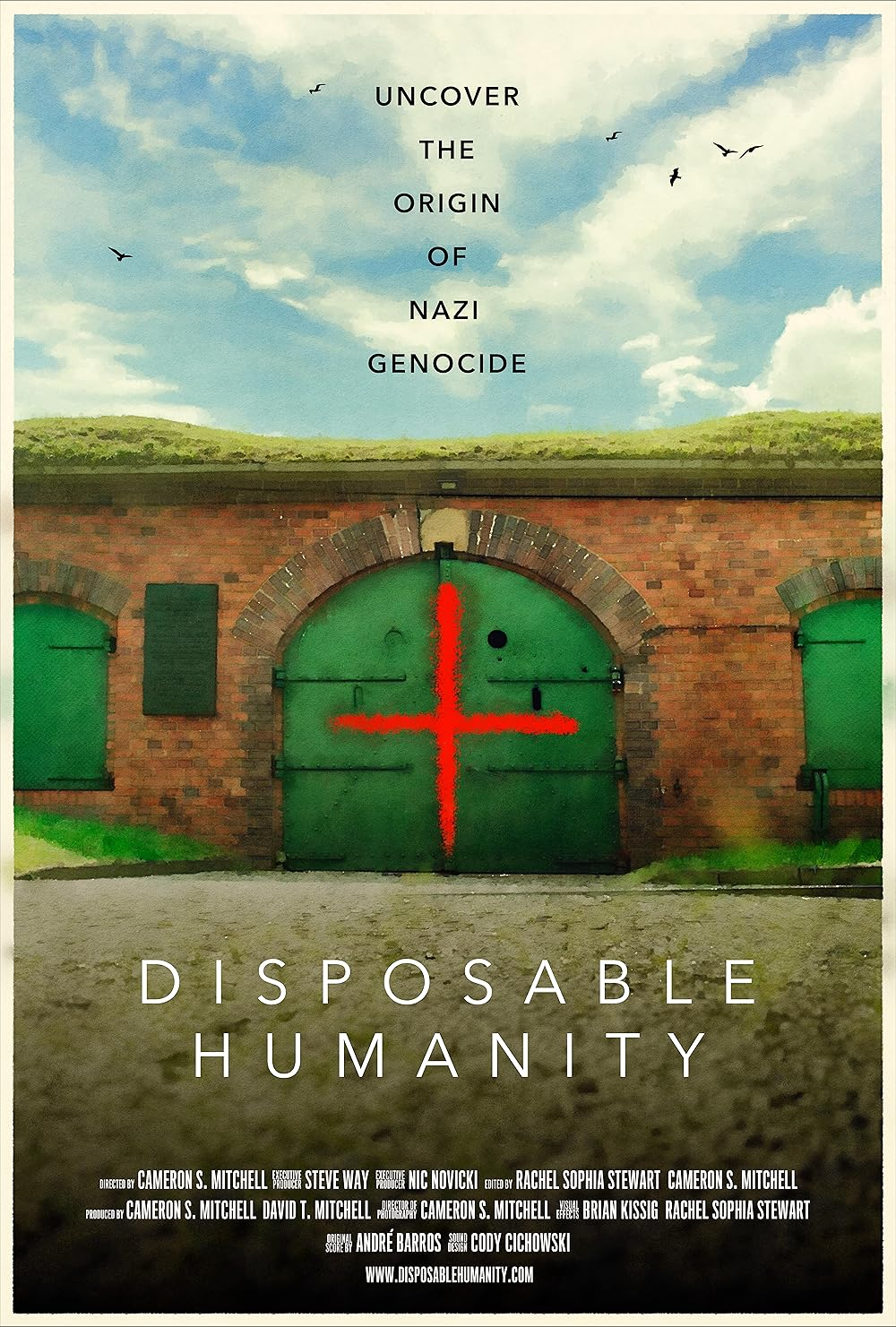

Disposable Humanity (2025)

So recently, the Centre Film Festival came to an end and I had the chance to attend one of the film screenings, Disposable Humanity, directed by Cameron S. Mitchell and showing at the Rowland Theater in Philipsburg. I was joined by my colleagues Dr. Forrest and Svetlana, and as we were making our way into the theater, we wanted to pose for a picture in front of the Film Centre Festival banner — and guess who took the photo? The director himself. Such an energetic and passionate being with love for what he does.

We honestly didn’t know what to expect as we were getting into the theater. Of course, we have some background knowledge on the Holocaust, but the film challenged our understanding by offering another perspective; one that narrates the experiences of people living with somatic and psychological dis/ability during Nazi Germany. If you want to avoid spoilers, I would encourage you to check the next screening near you, and I promise it will encourage you to rethink how we talk about dis/ability.

Aktion T4, as the director says, provided a blueprint that Nazi Germany would later use in their executions. The focus of the film, therefore, is centering voices of disabled people in Holocaust studies, and it is the hope of Cameron that this film will trigger conversations surrounding dis/ability not only as a historical event, but one that continues to be marginalised even today.

Speech by the Director

As a passionate film maker and speaker, cameron’s talk moved me and it was important to record this conversation to capture his thought process, family background and his imaginaries for the future. I have summarised the main points in my own words in part to avoid copyright infringment and also to accenuate the major themes that emerged from the discussion.

1. Cameron’s opening reflection

- Cameron begins by honoring a late disability scholar whose writing emphasized the need for more stories from disabled people—especially in difficult times. He shares that he first visited a Nazi killing site as a child, appearing in footage shown in the film. He argues that children should learn about this history early because disabled children have always been targets of oppressive policies. He ties current political rhetoric (like contemporary references to eugenics-era immigration laws) to the ongoing relevance of this past.

2. How the family began researching the T4 program

- While his parents were teaching disability studies in Germany in the 1990s, they gave a talk on American eugenics. An audience member told them—via a hesitant translator—that a similar program had taken place nearby. They went to the site, camera in hand, and began learning about the T4 euthanasia program, which at the time was largely unknown to them despite the extensive documentation of the Holocaust. The family has returned repeatedly, bringing students and scholars, linking remembrance with activism.

3. Brian’s reflections (actor/creative collaborator)

- Brian stresses how significant it was to work on the first feature-length film focused on this under-told chapter of the Holocaust. He describes contributing to the film’s restoration and visual texture, making archival material more accessible.

4. Challenges of making a film as disabled creators

- Cameron notes that practical barriers—mobility, cost, access to equipment—may be reasons why a feature film on this subject had not been made earlier. He explains how the film team worked to improve old footage and ensure viewers could follow the material without visual strain.

5. Finding descendants of perpetrators and witnesses

- Cameron explains that there are no living survivors of the T4 killing centers, because the program was designed to be fully lethal. He discusses the shame associated with sterilization and the difficulty in finding descendants willing to speak. He describes the disturbing repurposing of former killing sites, such as psychiatric facilities operating in buildings where people were murdered. He reflects on the layered, often jarring uses of these spaces today—like concerts held over grounds where ashes were scattered.

6. Nazi propaganda films and their contemporary echoes

- Propaganda film was crucial in normalizing sterilization and dehumanization. Cameron emphasizes that early Nazi plans did not include mass murder of Jews; the T4 program served as a prototype and training ground for the Holocaust. He highlights the direct pipeline of personnel, methods, and ideology from T4 to the Final Solution. Brian adds that disabled people were the first victims and the last to be remembered.

7. The influence of American eugenics

- Audience members note parallels between German and American histories, including long-running U.S. sterilization programs (e.g., North Carolina). Cameron says the film briefly addresses the U.S. role because of time constraints, but he stresses that Nazi policy drew heavily from American laws—especially California’s mass sterilizations. He reiterates that eugenic thinking was not unique to Germany but spread internationally.

8. Modern institutionalization and its dangers

- Another audience question raises the resurgence of support for institutionalizing disabled people. Cameron warns that institutions are historically tied to prisons and function as places to disappear people from public view. He argues that secrecy and isolation enable abuses, making visibility and public engagement crucial.

9. What’s next for the filmmakers

- Cameron is traveling with the film because independent works struggle to achieve distribution. He encourages audience members to support the film through festival votes and online reviews. For future creative work, he hints at developing a sci-fi horror film but wants to keep details private while it’s still forming. Brian is expanding into animation, 3D work, and music projects.